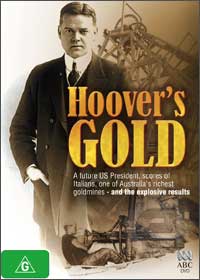

Hello, my name's Barry Strickland and welcome to my blog about the exploits of the young Herbert Hoover on the goldfields of Western Australia in the late 1890s and early 1900s. We've made a 52-minute documentary film about his experiences and his enduring Australian legacy called Hoover's Gold (Producer Marian Bartsch, Mago Films, 2005). I developed the concept and co-wrote the script with director Franco di Chiera.Hoover's Gold was commissioned by Australia's SBS Independent (Jennifer Crone, Executive Producer), with principal finance from Film Finance Corporation Australia and Screenwest (supported by Lotterywest). Reviewer Ron Banks, writing in The West Australian (23 November, 2005) noted that: “Hoover’s Gold offers fascinating insights into the development of the Goldfields and the significant role played by Hoover . . .[it] mounts its case in a sober, non-sensational yet extremely informative way . . . lively . . . crisp, tightly edited . . . Strickland and di Chiera’s documentary is also an intriguing account of life on the Goldfields for those immigrant families who pioneered one of the State’s most important sources of wealth.”

Hello, my name's Barry Strickland and welcome to my blog about the exploits of the young Herbert Hoover on the goldfields of Western Australia in the late 1890s and early 1900s. We've made a 52-minute documentary film about his experiences and his enduring Australian legacy called Hoover's Gold (Producer Marian Bartsch, Mago Films, 2005). I developed the concept and co-wrote the script with director Franco di Chiera.Hoover's Gold was commissioned by Australia's SBS Independent (Jennifer Crone, Executive Producer), with principal finance from Film Finance Corporation Australia and Screenwest (supported by Lotterywest). Reviewer Ron Banks, writing in The West Australian (23 November, 2005) noted that: “Hoover’s Gold offers fascinating insights into the development of the Goldfields and the significant role played by Hoover . . .[it] mounts its case in a sober, non-sensational yet extremely informative way . . . lively . . . crisp, tightly edited . . . Strickland and di Chiera’s documentary is also an intriguing account of life on the Goldfields for those immigrant families who pioneered one of the State’s most important sources of wealth.”

Hoover's Gold synopsis

In the remote goldfields of Western Australia – a land of “red dust, black flies and white heat” – an ambitious young American geologist embarked upon a remarkable career that would ultimately lead him to the White House as 31st President of the United States.

Herbert Hoover was just 23-years-old when London’s Bewick Moreing and Company shipped him off to Western Australia as an inspecting engineer, responsible for assessing the viability of the ever-growing portfolio of gold mines under its management. Arriving in Coolgardie in 1897, Hoover worked feverishly, appraising mines and scouting for new prospects for the company’s London investors. It was his identification of the Sons of Gwalia mine at Leonora as one “well worth securing control of” that was to be the turning point in his fortunes – and those of thousands of Italians and other southern Europeans who were to journey to Western Australia to work on the goldfields.

Installed by Bewick Moreing as the manager of the Sons of Gwalia mine, Hoover contracted several Italians as underground workers with the promise that, if they proved satisfactory, the way would be open to “the employment of many more”. He was determined to cut costs and undermine the growing strength of the trade union movement. He found the Italians “fully 20% superior” and “the rivalry between them and the other men is of no small benefit.”

In the decades to come, many Italians, mostly from Italy’s north, arrived in Western Australia to work on Bewick Moreing-controlled mines. The biggest and most enduring Italian community was associated with the Sons of Gwalia. It had rapidly become one of Australia’s deepest and richest mines, and being sufficiently distant from Kalgoorlie-Boulder’s ‘Golden Mile’, it had developed a character and significance all of its own.

Hoover’s Gold tells the parallel stories of the young Hoover and the Italian workers he championed. Filmed on location in Western Australia and the United States, we meet John Calegari, Renzo Mazza, Margo Patroni, Lucia Raymond, John Gandini and Tony Mateljan, whose families are all intimately (and at times tragically) associated with the Sons of Gwalia. Some were to be caught up in the infamous anti-foreigner riots that exploded in Kalgoorlie-Boulder on the Australia Day weekend of 1934.

We also hear from leading US and Australian experts – Tim Walch, Ron Limbaugh, Patrick Bertola, Richard Hartley and Criena Fitzgerald, all of whom have differing perspectives on Hoover, the Italians, and the Sons of Gwalia.

We witness evocative reconstructions of key moments in the goldfields experience of the Italians and the young Hoover. Ultimately, we discover how the changing fortunes of a remote Western Australian gold mine were to strangely mirror the career of the man who was to become America’s president at the onset of the Great Depression. Here's my detailed historical overview of Hoover's intimate association with the goldfields of Western Australia

1895 - 1896

Herbert Clark Hoover (born to Quaker parents in West Branch, Iowa, in 1874) graduates from California’s Stanford University with a degree in geology and $40 in his pocket. He toils as a labourer on gold mines before getting work with the prominent mining engineer Louis Janin.

Early 1897

Janin recommends Hoover for a position with London’s Bewick, Moreing & Co. They’re looking for an experienced engineer of at least 35 years of age to undertake inspections of their many gold mines in Western Australia.

March 1897

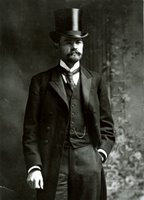

22-year old Hoover travels by train from California to New York, where he boards the SS Britannic bound for England. On the ship’s register he states his age as 36. He is growing a beard and by the time the Britannic docks at Liverpool on April 9, it is quite luxuriant. He hurries down to London, where he is interviewed by Charles Moreing (an Australian by birth), who afterwards marvels at how Americans are able to preserve their youth. But Moreing is satisfied Hoover is the man for the job and despatches him to Western Australia aboard the RMS Victoria.

May 1897 – April 1898

Hoover arrives at the West Australian port of Albany on May 13 and journeys by train to the capital Perth. Another train takes him 400 miles to Coolgardie, the birthplace of the now-extensive goldfields. This remote outback boom town is where Bewick, Moreing has its Australian regional headquarters.

Hoover’s ranked No. 4 among a staff of 53, with an annual salary of $5,000 plus expenses. He has his own valet and cook. As the inspecting engineer in charge of mine exploration and evaluation, he spends most of his time travelling (sometimes by camel) throughout the ever-expanding goldfields. On one trip, he inspects 18 mines in 18 days, while on another he looks at nearly 50 mines in just 10 days. He is already developing quite a reputation.

On one trip, he happens upon the fledgling Sons of Gwalia mine at Leonora, well over 100 miles north of Coolgardie. His geological training tells him this is a mine of enormous potential. He urges Bewick, Moreing to secure control and place him in sole command of its further development. He gets his wish on both counts.

May 1898 – November 1898

Not yet 24, Hoover is now the new superintendent of the Sons of Gwalia, with 250 men under his command. And he’s now on $12,500 a year with a share of the profits. He knows he has to make the mine realise the potential he identified in the report that convinced Bewick, Moreing to not only secure it but float it on London’s Royal Exchange as Sons of Gwalia Ltd. He sets about an ambitious redevelopment – upgrading plant and equipment, introducing new accounting systems, changing work practices and conditions, and obsessively pursuing cost savings in the name of efficiency and maximum profit. It’s all at breakneck speed and it’s not without its problems. He promptly squashes several strikes by disgruntled workers, and fuels long-term resentment by hiring Italian workers in preference to ‘Britishers’. And he’s already being hailed by the press, with London’s Financial Times declaring him “one of the ablest mining engineers in Western Australia”.

Ernest Williams, head of Bewick, Moreing’s Western Australian operations is not so impressed. He dislikes “the young Yankee upstart” and suspects he may be gunning for his job. He’s right. Hoover attempts to engineer a staff revolt against Williams.

In a letter to his brother Tad, Hoover writes, “He [Williams] is quite the most complete scoundrel I have ever met, and it's a question of fight or be done up behind my back. Between ourselves, they are a crowd of Sons of Bitches from stem to stern. It just happens that Charles Moreing's business can't run without me and I will force him to make me managing director of Australia or tell him to go to the devil.”

In London, Moreing is aware of what’s going on. He doesn’t want local fall-out from dismissing Williams, nor does he want to lose his ambitious and talented American. He resolves the situation by keeping Williams where he is and by offering Hoover a new opportunity in China where the company is seeking to develop new coal and gold-mining concessions. Hoover accepts the new challenge – and an increase in salary and conditions. The Sons of Gwalia, forever associated with Hoover, will become one of the 10 richest gold mines in Australian history and the mine from which Bewick, Moreing “made the most profit of any business we did.”

December 1898

All the while that Hoover’s been in Western Australia, he’s been financially supporting his brother Tad, sister May and cousin Harriette back in America (through the auspices of his Stanford friend and lawyer Lester Hinsdale). And he certainly hasn’t forgotten his Stanford sweetheart, the remarkable Miss Lou Henry, who was Stanford’s (and possibly the USA’s) first-ever female geology graduate. On packing up at the Sons of Gwalia and travelling to Perth in preparation for his journey to China via London and the US, Hoover cables Lou with four words: “Will you marry me?” She replies with one: “Yes.”

January 1899 – November 1901

Hoover arrives in London for a briefing on the China job, then proceeds to New York and across the continent to Monterey in California where he marries Lou Henry on February 10. The next day they sail out of San Francisco for China.

Hoover has a dual role in China as Bewick, Moreing’s representative and as the Chinese government’s chief engineer in its Bureau of Mines, responsible for Chihli and Jehol provinces. He and Lou are based in Tientsin and this is where they are during the anti-foreign nationalist insurrection known as the Boxer Rebellion (June-August 1900). Along with hundreds of foreign families, they are trapped in the European compound, defended by just a few soldiers. Hoover helps direct the construction of barricades, while Lou is busy attending to the sick and wounded. Their house is hit by mortar fire and Lou narrowly escapes a bullet, while hundreds others are killed. In America, there are press reports that the Hoovers have lost their lives. But after ten long weeks, relief forces finally arrive and they manage to escape China, taking a German mail boat to Europe.

Once things have settled down, Lou initially remains in London while Hoover returns to his unfinished work in China. He succeeds in turning a struggling coal mining and export enterprise into a highly profitable one (the Chinese Engineering and Mining Company, which he’s floated in London), but not without some controversy and associated scandal. Indeed, some years later (in 1905), Chang Yen Mao, Director-General of mines for the Chinese Government will bring court action against Hoover, accusing him and his associates of tricking him out of some valuable mining property. An out of court settlement of $750,000 is made.

By the time Hoover leaves China in October 1901 he is reputedly the “richest salaried man of his age in the world”, but he also has $250,000 in cash from the sale of some of his Chinese coal mining stocks.

The Hoovers return to California in October 1901, before once again heading to London.

December 1901 – April 1902

Back in London, Hoover is rewarded for his efforts with a partnership in Bewick, Moreing & Co. Moreing retains 50% ownership, with Hoover being given a 20% share along with A. Stanley Rowe, and Thomas Wellstead a 10% stake. Hoover’s primary responsibility is overseeing the firm’s far-flung mines, both as engineer and administrator. He does this from his London office via cables and written correspondence, directing all aspects of global operations. But he is also constantly travelling, inspecting the mines he and his partners have been contracted to manage. With so many of the richest and most profitable properties being in Western Australia, he returns regularly to the ‘Golden West’. On Kalgoorlie’s Golden Mile, the firm has management of some of the glamour mines, while to the north, the Sons of Gwalia and the Great Fingall (at Day Dawn near Cue) are jewels in the crown.

In January 1902, Hoover, accompanied by Lou, returns to Western Australia for the first time since his departure in 1898. It’s a blisteringly hot summer, but Hoover’s no longer “an insecure Yank trying to hide his age behind a beard . . . he is a general now, not a lieutenant.” He’s prepared to give orders and have them obeyed. No more of the disrespectful “Hail Columbia” (a reference to his initials) that he endured from some detractors during his Sons of Gwalia days.

Much has changed. The speculative boom of the ‘Roaring Nineties’ (which saw over 800 gold mining companies registered on the London exchange) has burst, leaving only 140 survivors. Many are under Bewick, Moreing’s firm control yet their managers fear Hoover’s visit. They know his reputation for insisting on the highest standards and the greatest efficiencies.

London has just been rocked by the sensational collapse of the massive Whitaker Wright investment empire that includes two of the Golden Mile’s richest mines – the Lake View Consols and the Ivanhoe. Wright has fled to American and the English authorities are attempting extradition. Aboard the ship the Hoovers are travelling on is 43-year-old Francis Govett, a prominent stockbroker. Disgruntled Lake View shareholders have just deposed Wright’s dummy directors and have appointed Govett the chairman of the new board. He’s on his way to Kalgoorlie to inspect the mine and to make decisions as to its future. Govett becomes friendly with Hoover and is impressed by his knowledge and no-nonsense approach to his job. When he and the Hoovers arrive in Kalgoorlie, Govett hands management of the Lake View Consols over to Bewick, Moreing. This is to be a turning point in the firm’s fortunes, leading to significant expansion and a lifelong collaboration and friendship between Govett and Hoover.

Hoover wastes little time in drastically overhauling Bewick, Moreing’s senior Western Australian personnel. He sacks many mine managers, engineers and metallurgists and replaces them with Americans, including a number of Stanford graduates. Some suspect that Hoover is taking pleasure in sacking all those who remained loyal to Ernest Williams during their 1898 dispute and who had “not properly appreciated him”.

In their two-and-a-half month visit (mid-January to early-April), the Hoovers travel 3,500 miles by train, horse and buggy and camel.

May 1902 – August 1903

Back in London there’s trouble. Big trouble. Over Christmas 1902, it emerges that one of Hoover’s fellow Bewick, Moreing directors, Stanley Rowe, has been trading in forged Great Fingall shares. A labyrinth of associated fraudulent activity amounts to tens of thousands of pounds. Rowe has disappeared without trace and soon the scandal is in all the papers.

Charles Moreing is away on business in China and to save the company and its reputation, Hoover and remaining director Wellstead know they have to act immediately and boldly. Without first consulting Moreing, Hoover announces to the press that the firm will make good the $1,000,000 in losses incurred by the victims of Rowe’s fraud. Hoover argues that while the company is not legally responsible for Rowe’s crimes or the victims’ losses, it recognises a moral obligation to make good the private misdemeanours of one of its directors through the restitution of the embezzled funds. When Moreing returns from China, he’s fuming and relations between him and Hoover are irrevocably tarnished. But Hoover’s strategy works – the press responds positively, praising the company for its quick action. Ironically, Bewick, Moreing’s reputation and its business is actually enhanced. However, Hoover personal contribution to the victims of Rowe’s fraud amounts to around $200,000 – money he’s worked tirelessly to accumulate. Indeed, he has sailed close to financial ruin. To make matters worse, one of the victims suggests that Hoover was a co-conspiritor in Rowe’s fraud and the matter goes to court, not to be finally resolved, in Hoover’s favour, until 1905.

September 1903 – December 1906

Hoover, Lou and their newborn son leave London for another inspection trip to Western Australia. Hoover takes to Kalgoorlie one of the first automobiles seen on the goldfields, allowing him to travel up to 125 miles a day. He drives it to the Sons of Gwalia at Leonora and on to the Great Fingall at Cue. He is pleased with much of which he sees. His new American recruits are achieving excellent results and bringing a higher standard of expertise and efficiency to Bewick, Moreing’s operations. The number of men employed is declining but production increasing, thanks to new labour-saving machinery and streamlined work practices. The press cannot sing Hoover’s and Bewick, Moreing’s praises highly enough, with Hoover courting journalists at every opportunity and contributing articles himself under various pseudonyms. There was “no cleverer engineer in the two hemispheres”.

Yet within Western Australia there are those who are highly critical of Hoover. Bewick, Moreing is accused of being a monopoly in the service of London’s money men. There are demands for Western Australian directors to be on the board of every gold mining company and an end to what appears to be a pro-Italian employment policy. Unions call for a Royal Commission to look closely at the firm’s employment policies and the Kalgoorlie Miner refers to an “alien invasion” and declares that “unless stringent measures are adopted the British worker will be gradually ousted by the foreign element”. Hoover goes on record stating, “the fly in the West Australian ointment lies in the growth of the Socialistic element in the Labour Party and the legislation for which they have been responsible”.

The Royal Commission is held and finds that while the overall number of Italian miners is small, half of them are concentrated in just five mines all run by Bewick, Moreing (including the Sons of Gwalia, Great Fingall and Lancefield mines). At these mines, it is shown that the percentage of Italians employed ranges from 19% to 39% of the total workforce. This is enough for the commissioners to state that “experienced British miners are refused work over and over again, while Italians – often newly come to the State – are being freely accepted”. The Royal Commission urges stringent restrictions on the employment of aliens unable to speak English fluently (as safety underground requires it) and recommends that no mine should have more than a one-seventh “alien” component in its workforce without the express permission of the Minister for Mines.

But this is not the only Royal Commission in progress. Another is exploring a far more complex case – stemming from a meeting on board the ship that Hoover was returning to England upon following his 1903 visit to Western Australia. A fellow passenger is another American, Ralph Nichols, who’s general manager of the Great Boulder Perseverance Mine on the Golden Mile. They discuss the possibility of Bewick, Moreing assuming management of the mine. When Hoover arrives in London, negotiations commence but it becomes clear that the Great Boulder’s directors actually want Bewick, Moreing to bail their chairman, Frank Gardner, out of a difficult financial situation. An aggressive speculator, Gardner’s in need of cash and he wants to sell 60,000 Great Boulder shares. Could Bewick, Moreing buy his shares in return for management of the mine?

Bewick, Moreing agree, with the firm itself buying 38,500 of Gardner’s shares, costing a quarter of a million dollars. It’s an uncharacteristic move, particularly without a prior inspection of the mine’s current status and future potential – and given that stock market “bears” have been claiming for months that the mine can’t possibly maintain its high monthly output. Hoover is certain that his fellow countryman Ralph Nichols is a reputable engineer and that his estimates of a yield of better than an ounce to the ton will hold true. They don’t. W.A. Prichard, Bewick, Moreing’s general manager at Kalgoorlie (another Stanford man and a Hoover appointee), confirms that Nichols has over-estimated the value of reserves by at least 30% and states that the richest sections of the mine are being gutted in order to maintain an artificially high output. Hoover instructs Prichard to “thoroughly sample” the mine in Nichols’ absence but to disclose nothing publicly. This happens, with another of Hoover’s American appointees, W.L. Loring, undertaking the sample. The results are devastating. Rather than the 400,000 tons of ore reserves claimed by Nichols, the mine had less than 140,00 tons.

It’s disaster time. Hoover delivers the news to the Great Boulder’s board of directors, who seek clarification (and receive it) but choose not to immediately inform their shareholders. Within 24 hours, Great Boulder shares plummet on the London exchange. What’s going on? Who is leaking information or off-loading shares through insider trading? Moreing, Hoover and Wellsted immediately decide to unload their 38,500 shares. This is either as or just before Great Boulder shareholders are being officially informed by the board of the situation. They receive less than half what they’ve paid to Gardner as part of the management deal. In selling hurriedly, they spark a scandal. But they believe they’ve been deliberately duped by ore estimates that were flagrantly erroneous – and they’re probably right.

But the finger gets pointed in their direction. Moreing claims that since it was clear that the Great Boulder directors had clearly lied about the mine’s ore reserves, it was legitimate for Bewick, Moreing to cut its losses by acting decisively. He and Hoover feel they have been deliberately misled. This prompts a Royal Commission in Western Australia. Its report, issued in December 1904, strongly criticises all parties, most particularly the Great Boulder’s board of directors. However, it also notes that it was odd that Hoover and his partners did not register their firm’s 38,500 shares in the firm’s own name, concluding that Bewick, Moreing did not want it known that they were holding shares in a mine over which they’d just been given management. In what is ultimately a complicated and damming finding, Hoover is nevertheless pleased that he personally has not been blamed for mismanagement of the mine. It’s another narrow escape and Hoover later claims that the commission's report demonstrates Bewick, Moreing’s “complete integrity of engineering and management”. However, he’s again sobered by the dangers of mingling professional engineering with “trafficking in shares”.

During his 1905 visit to the ‘Golden West’, Hoover tells the press that “this State [Western Australia] cannot make progress in mining without the aid of the British capitalist – it is absurd to talk otherwise.” He is in a bullish mood, talking up the benefits of having the likes of Bewick, Moreing managing its premier mines. But he threatens that Bewick, Moreing will “shut up shop” if there’s not a more conducive environment in which it can do business. Late in 1905, the Labour government loses power and Hoover welcomes the advent of “more Conservative Government”. “The colony has,” he says, “freed itself from a labour government, and more can now be hoped for in terms of the development of the State’s resources.” But he is still frustrated by the constant problems associated with gold mining in the Golden West – and is becoming increasingly intolerant of Charles Moreing. He wants the firm to buy and operate mines for itself, rather than just manage them. Moreing does not.

January 1907 – July 1908

Externally, Hoover has achieved great success, hailed internationally. He’s still a young man and he’s making in excess of $100,000 a year. In January 1907, he commences a six-month Australia visit, leaving Lou (who’s pregnant with their second child) behind in London. This is to be his final visit “down under” for Bewick, Moreing. Hoover wants to break loose, branch out on his own. He’s no longer just interested in Australia but has his eyes set on the likes of Burma and the new prospects for oil exploration. Moreing privately claims Hoover is suffering from “consumption of the brain” but suspects he will finally lose his brilliant but difficult American. Feigning bad health, Hoover announces his retirement from Bewick, Moreing, taking effect on June 30 1908. He sells his share in the company for around $150,000 to W.L. Loring, who is now the firm’s general manager in Australia. Hoover agrees not to practice his profession as a mining engineer anywhere in Great Britain or the British empire for the next ten years without Bewick, Moreing’s consent. His fortune, while not grandiose, is considerable and still growing. His reputation is solid. He’s 34 years old. He’s free and finally his own man . . . or is he?

Postscript

1909 – 1914

On leaving Bewick, Moreing in 1908, Hoover becomes an even higher-flying international engineer-financier and venture capitalist, branching out into oil in addition to his continuing focus on precious metals. Still based in London, he's frequently in dispute with Charles Moreing over supposed breaches in his severance contract, leading to several courtroom battles. When war breaks out in 1914, thousands of Americans are stranded in Europe and he's asked by the US ambassador to the UK to co-ordinate their evacuation to London and their safe return to the US. This marks the beginning of the public service / humanitarian phase in his career.

Yes, we're now counting down to the national broadcast of HOOVER'S GOLD on SBS Television on Thursday 27 July at 8.30pm (the Storyline Australia time-slot).

Yes, we're now counting down to the national broadcast of HOOVER'S GOLD on SBS Television on Thursday 27 July at 8.30pm (the Storyline Australia time-slot).